PS I synthesize here in my own words what King teaches, re-write all his example programs, character by character, solve all the C exercises he hands out, and if I do not understand something fully I use Bermudez' CP: AMA Study Guide to find clarification. I comment to what King teaches cursively. I do not copy-paste anything from the book!

CPaMA 1Ed - Page 009 to 020 - 4.19% Completion

CPaMA 1Ed - Page 009 to 020 - 4.19% Completion

2 C Fundamentals

In chapter 2 King introduces the basic concepts of C that will be treated more in depth later on in the book.

1 Writing a Simple Program

King shows what a simple small C program looks like:

This program will be labeled as 'pun.c'.

#include <stdio.h>

main ()

{

printf ("To C, or not to C: that is the question.\n");

}

<studio.h> is the standard input/output library, and we use #include to make sure we can call functions from it.

The executable code is written inside 'main', which represents the "main" program. In this example the program consists of the command to print (printf) the message between (" ") on the screen, where \n tells the printer to advance to the next line.

Printf is a function in the standard I/O library and by writing printf we call it in to action so to speak.

Compiling and Linking

The steps from having a program text file to having an executable program.

- preprocessing

The preprocessor edits the program according to the commands starting with the # symbol (directives)

- compiling

The modified program then moves to the compiler, which translates it into machine instructions (object code).

- linking

The linker combines the object code with additional code needed to get an executable program. This includes library functions.

Most of these steps are automatic.

An IDE does it all automatically, gnu GCC requires only a compilation command.

<studio.h> is the standard input/output library, and we use #include to make sure we can call functions from it.

The executable code is written inside 'main', which represents the "main" program. In this example the program consists of the command to print (printf) the message between (" ") on the screen, where \n tells the printer to advance to the next line.

Printf is a function in the standard I/O library and by writing printf we call it in to action so to speak.

Compiling and Linking

The steps from having a program text file to having an executable program.

- preprocessing

The preprocessor edits the program according to the commands starting with the # symbol (directives)

- compiling

The modified program then moves to the compiler, which translates it into machine instructions (object code).

- linking

The linker combines the object code with additional code needed to get an executable program. This includes library functions.

Most of these steps are automatic.

An IDE does it all automatically, gnu GCC requires only a compilation command.

Gnu GCC existed in 1996 and it still exists in 2025, and is mostly used in Linux os'es but can also be used in MS Windows via minGW. I use an older version of GCC, via, minGW, for Windows XP 32bit.

Currently the command to compile a c text file is, both in Linux and Windows command line, as follows:

$ GCC example.c -o example.exe

King goes on to say that there are basically two options to create an .exe file: either with IDE or manually, in cmd line.

2 The general Form of a Simple Program

directives

main ()

{

statements

}

King describes how C uses { } for what other high level programs call 'begin' and 'end'.

This was the case with non-c languages in 1996, however because nearly all languages in 1996 are derived from c they all use curly brackets.

But as King says, this is a good example of how C relies on abbreviations and special symbols, which makes it concise but also cryptic, less human-readable.

King explains how every C program largely consists of three key features:

- directives

- functions

- statements

Directives

Are commands for the preprocessor. They always start with # and are one line long without semi colon or special marker at the end.

#include <stdio.h> is the directive in pun.c.

It states that the data in <stdio.h> is included in pun.c.

stdio.h is a default C library that governs / programs input/output.

C has several possible directive headers. More than one can be added.

Functions

In some other (older) languages these are called 'procedures' or 'subroutines'.

Functions are what makes up a program in C. A C program is a collection of functions.

There are 2 types of functions, those that are part of the C implementation and those that the programmer adds.

There are many optional functions in C but the 'main' function is obligated for a C program to run.

A function returns a value.

#include <stdio.h>

main ()

{

King describes how C uses { } for what other high level programs call 'begin' and 'end'.

This was the case with non-c languages in 1996, however because nearly all languages in 1996 are derived from c they all use curly brackets.

But as King says, this is a good example of how C relies on abbreviations and special symbols, which makes it concise but also cryptic, less human-readable.

King explains how every C program largely consists of three key features:

- directives

- functions

- statements

Directives

Are commands for the preprocessor. They always start with # and are one line long without semi colon or special marker at the end.

#include <stdio.h> is the directive in pun.c.

It states that the data in <stdio.h> is included in pun.c.

stdio.h is a default C library that governs / programs input/output.

C has several possible directive headers. More than one can be added.

Functions

In some other (older) languages these are called 'procedures' or 'subroutines'.

Functions are what makes up a program in C. A C program is a collection of functions.

There are 2 types of functions, those that are part of the C implementation and those that the programmer adds.

There are many optional functions in C but the 'main' function is obligated for a C program to run.

A function returns a value.

#include <stdio.h>

main ()

{

printf ("To C, or not to C: that is the question.\n);

return 0;

return 0;

]

Statements

Statements are the commands out of which a function consists.

Pun.c has two statements in it:

The printf function call statement and the return statement.

In pun.c the printf statement calls upon the printf function to print a string:

printf ("To C, or not to C: that is the question.\n");

In C a statement is only treated as a statement if it ends with semi-colon, except in the case of the compound statement. Statements need a semi-colon because they can cover several lines (a statement ends when the semi-colon shows up), a directive does not need a semi-colon, since it never covers more than one line.

Statements

Statements are the commands out of which a function consists.

Pun.c has two statements in it:

The printf function call statement and the return statement.

In pun.c the printf statement calls upon the printf function to print a string:

printf ("To C, or not to C: that is the question.\n");

In C a statement is only treated as a statement if it ends with semi-colon, except in the case of the compound statement. Statements need a semi-colon because they can cover several lines (a statement ends when the semi-colon shows up), a directive does not need a semi-colon, since it never covers more than one line.

Printing Strings

the printf call makes the program use the printf function to print a string literal on the screen

- string literal

A series of characters enclosed in double quotation marks. Only the characters are displayed when executing.

We tell printf to jump to a new line by including the \n symbol, which is called the new-line character.

These statements:

printf ("To C, or not to C: ");

printf ("that is the question.\n");

will, together, produce exactly the exact same output as

printf ("To C, or not to C: that is the question.\n);

King writes that the new-line character can appear more than once in a string literal.

We can write

printf ("Brevity is the soul of wit.\n --Shakespeare\n");

to print the authors name underneath his statement:

Brevity is the soul of wit

--Shakespeare

Comments

Text in the program that is meant as information and is supposed to not have any effect on the program is called a comment. /* is the start of a comment and */ the end.

/* This is a comment */

Example of how comments could be used for pun.c::

/* Name: pun.c */

/* Purpose: Prints a bad pun. */

/* Author: K. N. King */

/* Date written: 5/21/95 */

#include <stdio.h>

main ()

{

/* Purpose: Prints a bad pun. */

/* Author: K. N. King */

/* Date written: 5/21/95 */

#include <stdio.h>

main ()

{

printf ("To C, or not to C: that is the question.\n");

return 0:

return 0:

]

Comments can run over more than one line . All that is written between /* and */ will be ignored by the program. Like this:

Comments can run over more than one line . All that is written between /* and */ will be ignored by the program. Like this:

/* Name: pun.c

Purpose: Prints a bad pun.

Author: K. N. King]

Author: K. N. King]

Date written: 5/21/95 */

However this might be a bit more readable:

/* Name: pun.c

Purpose: Prints a bad pun.

Author: K. N. King

Author: K. N. King

Date written: 5/11/95

*/

*/

Some put boxes around comments, like this:

/***************************************************

* Name: pun.c *

* Purpose: Prints a bad pun. *

* Author: K. N. King *

* Date written: 5/21/95 *

****************************************************/

Some do the same but simplified:

/*

* Name: pun.c

* Purpose: Prints a bad pun.

* Author: K. N. King

* Date written: 8/21/95

*/

* Purpose: Prints a bad pun. *

* Author: K. N. King *

* Date written: 5/21/95 *

****************************************************/

Some do the same but simplified:

/*

* Name: pun.c

* Purpose: Prints a bad pun.

* Author: K. N. King

* Date written: 8/21/95

*/

A comment in the same line as program code is also possible and is sometimes called a 'winged comment'.

main () /* beginning of main program */

Forgetting to close the comment may cause the compiler to ignore part of a program.

Variables and Assignment

A variable serves as a placeholder for a specific data item.

- enabling the program in which the variable is used to change the object of its operation on the fly,

and also

- making the same program it (re)usable for different data items with which you want to do the same operation.

A variable always has a type that needs to be specified and which must be in accord with the item that is assigned to the variable. This type will determine for what it will be used for, and how.

To begin with, the book starts with two variable: types: int and float.

The type of a numeric variable determines:

- the smallest number the variable can store

- the biggest number the variable can store

- whether or not numbers can be used after the decimal point

int (integer) can store:

- a whole number up to a limited amount, which depends on the computer.

On some this is 32,767. (at the time of writing)

float (floating-point) can store:

- decimal digits

However they

Forgetting to close the comment may cause the compiler to ignore part of a program.

Variables and Assignment

A variable serves as a placeholder for a specific data item.

- enabling the program in which the variable is used to change the object of its operation on the fly,

and also

- making the same program it (re)usable for different data items with which you want to do the same operation.

A variable always has a type that needs to be specified and which must be in accord with the item that is assigned to the variable. This type will determine for what it will be used for, and how.

To begin with, the book starts with two variable: types: int and float.

The type of a numeric variable determines:

- the smallest number the variable can store

- the biggest number the variable can store

- whether or not numbers can be used after the decimal point

int (integer) can store:

- a whole number up to a limited amount, which depends on the computer.

On some this is 32,767. (at the time of writing)

float (floating-point) can store:

- decimal digits

However they

- require more space in memory than int variables

- are slower

- less accurate

- are slower

- less accurate

Declarations

Variables most be 'declared' to make them effective.

The rules for declaration:

First we

1) specify the type

then

2) we specify the name

of the variable.

Examples on the types int and float:

int height;

float profit;

The content of a variable name is meaningless from the standpoint of a program but for the programmer it is useful to use a name that is related to the purpose of the variable.

int height

is a variable of the type int so it can store an integer value which means a whole number.

float profit

is a variable of the type float meaning it can hold a floating-point value, which means it can hold a decimal number.

Variables of the same type can be declared together:

int height, length, width, volume;

float profit, loss;

A declaration, whether single or as a combination, always has to be concluded with a semi-column in order for it to take effect when running.

Variables most be 'declared' to make them effective.

The rules for declaration:

First we

1) specify the type

then

2) we specify the name

of the variable.

Examples on the types int and float:

int height;

float profit;

The content of a variable name is meaningless from the standpoint of a program but for the programmer it is useful to use a name that is related to the purpose of the variable.

int height

is a variable of the type int so it can store an integer value which means a whole number.

float profit

is a variable of the type float meaning it can hold a floating-point value, which means it can hold a decimal number.

Variables of the same type can be declared together:

int height, length, width, volume;

float profit, loss;

A declaration, whether single or as a combination, always has to be concluded with a semi-column in order for it to take effect when running.

Declaration must precede statements in a program, like this:

main ()

{

declarations

statements

statements

}

For readable styling it is good to leave a line between the declarations and the statements.

Assignment

After declaring the type of a variable we then assign a value to it: with the = character:

height = 8;

length = 12;

width = 10;

Once assigned the variable can be used to assign the same value to other variables as follows

volume = height * length * width;:

A formula can also be assigned to a variable. This is called an expression in C. An expression can consist of constants, variables and operators.

Printing the Value of a Variable

After we declared a variable and assigned a value to it as such

Height: n

We can print this value as follows:

printf ("Height: %d\n", height);

%d serves as a placeholder for the value assigned to the variable height, which will be printed in the output medium.

%d only works for int variables. %f works for float variables. %f by default prints 6 digits after the decimal point. To make %f print a certain number of digits after the decimal point, let's say 2, we write as follows:

printf ("Profit: %.2f\n", profit);

We can add an unlimited amount of variables inside a single printf callFor readable styling it is good to leave a line between the declarations and the statements.

Assignment

After declaring the type of a variable we then assign a value to it: with the = character:

height = 8;

length = 12;

width = 10;

Once assigned the variable can be used to assign the same value to other variables as follows

volume = height * length * width;:

A formula can also be assigned to a variable. This is called an expression in C. An expression can consist of constants, variables and operators.

Printing the Value of a Variable

After we declared a variable and assigned a value to it as such

Height: n

We can print this value as follows:

printf ("Height: %d\n", height);

%d serves as a placeholder for the value assigned to the variable height, which will be printed in the output medium.

%d only works for int variables. %f works for float variables. %f by default prints 6 digits after the decimal point. To make %f print a certain number of digits after the decimal point, let's say 2, we write as follows:

printf ("Profit: %.2f\n", profit);

printf (Height: %d Length: %d\n", height, length);

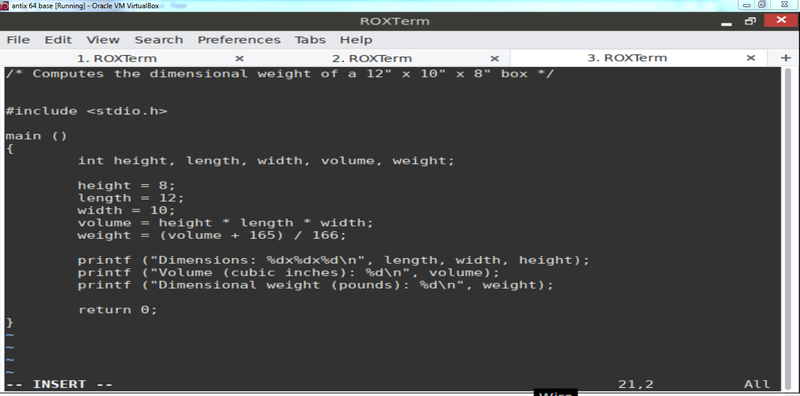

Computing the Dimensional Weight of a Box

This first full program of the book is meant to calculate the price of post packages for a company X. Packages have all kinds of weights and sizes. When calculating the price of such packages both weight and size are considered since both parameters affect the company's storage and transport costs. The parameters are expressed in units. One weight unit resembles one pound of weight and one volume unit resembles166 cubic inches. Whichever unit amount is higher is used for calculating the fee. If the number of weight units is higher than the number of volume units the fee will be based on the weight units. If the number of volume units is higher then the fee will be based on the number of volume units.

The book states that to calculate the number of volume units it would be intuitive to divide the volume / 166. However in C, when dividing integers (whole numbers) the result will be an integer. To accomplish this, the operation will ignore decimal digits, effectively rounding down the outcome. This is not what the company wants, as they have the rule in place to round fractional outcomes upward. Thus we need a program that uses an alternative calculation that will deliver a rounded up number...

The program in the book solves this as follows:

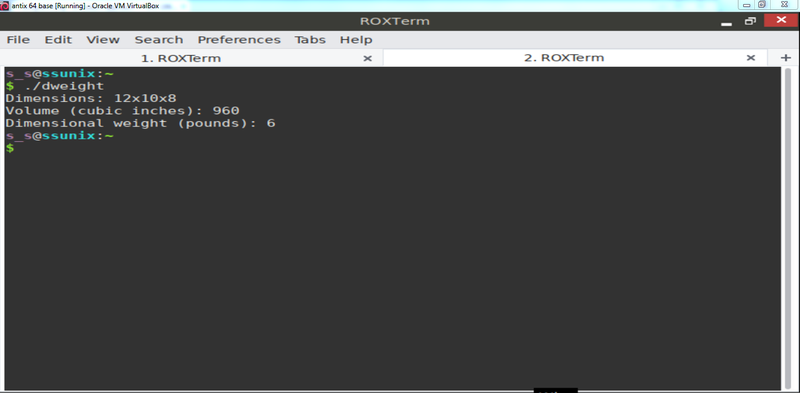

The output of this program is:

The program adds 165, effectively lifting the outcome 0.9835... upward, above the next whole number, so that the new outcome, after rounded down, will reflect the initial number rounded up, while assuring not to add a whole number to the outcome by remaining below 100%.

Initialization

At the very beginning of a program, when a variable is declared but has not yet a value assigned to it the program is often automatically set to 0, but not always, and can have any random value attached to it. Once we assign a value to the variable then that will stay with it until we assign again a new value. To avoid unpredictable values we can assign a value in the same sentence as the declaration command. Like this:

int height = 8;

8 in this case is called an initializer.

As stated before (I think) any number of variables can be initialed in the same declaration:

int height = 8, length = 12, width = 10;

Each variable requires its own initializer.

Here:

int height, length, width = 10

only width is initialized.

Printing Expressions

printf can output any numeric expression. This quality allows for reduction of statement length

volume = height * length * width;

printf ('%\n" volume);

can be written as

printf ("%d\n", height * length * width);

"Wherever a value is needed, any expression of the same type will do"

The point of the matter

Okay I read further on this matter and I might got the point:

In C, it is not allowed to use more than one data type within one expression. This rule ensures that operations are performed correctly and consistently. Data types have a specific type and behavior and mixing them can cause errors and undefined behavior.

However, I still find the sentence strange and not fully applicable to this acknowledgement, and so maybe I still did not get it right. But I will continue with the text for now and keep this matter in mind, until I am sure that I understood what it meant.

Reading Input

The dweight.c program only calculates the dimensions of one box. We need a program that can calculate based on variable input so that employees can calculate a fee for of each package that they are confronted with, at the spot.

For printing output printf is used, for input scanf is used:

The f stands for formatted.

scanf ("%d, &i); /* reads an integer; stores into i */

%d = tells scanf to read input that represents an int. i is an int variable into which we want scanf to store the input. King says that he will explain the & symbol later since it is hard to explain at this point and that it is usually required when using scanf.

scanf ("%f", &x); /* reads a float value, stores into x */

%f is meant for variables of type float. In this line %f tells scanf to look for an input value in float format (the number may contain a decimal point, but this is not necessary. Thus float can contain both integer as well as fractional numbers.